Today we’re looking at the XLMRat malware. It is a remote access trojan (hence the RAT part) built to be small, sneaky, and stupidly persistent. It typically rides in via phishing or social engineering, often disguised as something mundane, like a JPG or TXT file. It targets Windows systems and speaks fluent PowerShell.

It’s popular among low-effort attackers looking for ready-made tools that still pack a punch. Especially in campaigns targeting individuals or small orgs where endpoint hygiene is weak. There’s a block with more information at the end of this post ⬇️

The challenge is presented by CyberDefenders (https://cyberdefenders.org) and can be found here: https://cyberdefenders.org/blueteam-ctf-challenges/xlmrat.

Scenario

A compromised machine has been flagged due to suspicious network traffic. Your task is to analyze the PCAP file to determine the attack method, identify any malicious payloads, and trace the timeline of events. Focus on how the attacker gained access, what tools or techniques were used, and how the malware operated post-compromise.

Note: This post is not sponsored by or affiliated with CyberDefenders.

Tools I used

- Wireshark – for diving into the packet capture file

- VirusTotal – for confirming suspicions and getting related and relevant information

- Python 3 – for decoding, hashing, and extracting

⚠️ Note: I recommend using a VM or isolated analysis box. This malware isn’t theoretical, it’s live and capable ☣️

⚠️ ⚠️ Note: If you’re on Windows, do use an isolated analysis box!

First look

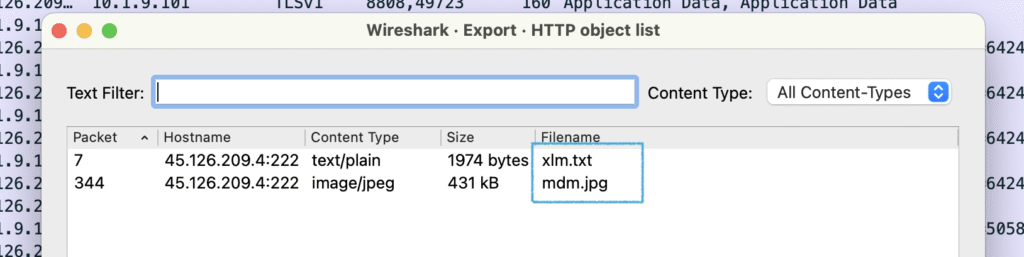

Before answering the questions, I checked the PCAP file for HTTP traffic and any files available.

File → Export Objects → HTTP gives us 2 files:

xlm.txtmdm.jpg

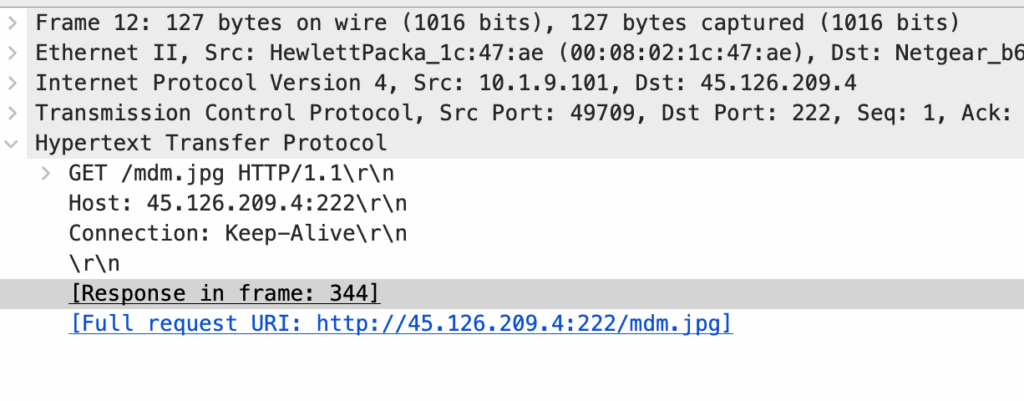

Q1: The attacker successfully executed a command to download the first stage of the malware. What is the URL from which the first malware stage was installed?

The first file downloaded, xlm.txt is a stage 1 dropper. But not the malware itself.

It seems to do 2 things:

- reconstruct an obfuscated PowerShell command from fragments

- invoke PowerShell with obfuscation and execution bypass options to run it

xlm.txt dynamically builds a PowerShell command. The PowerShell command then downloads and executes the actual payload being mdm.jpg.

Since we’re asked about the URL “from which the first malware stage was installed”, the correct answer is the URL of mdm.jpg.

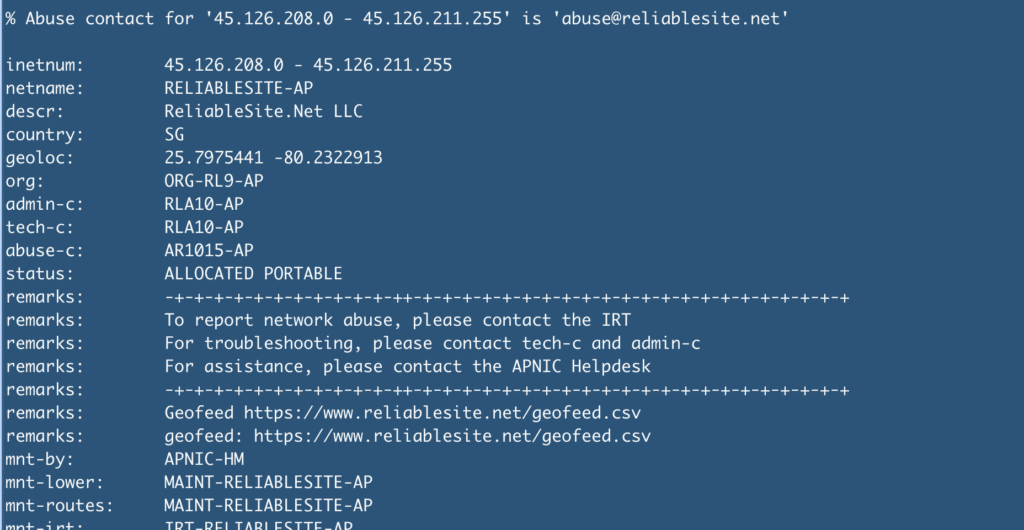

Q2: Which hosting provider owns the associated IP address?

The IP in question is 45[.]126[.]209[.]4

45[.]126[.]209[.]4A quick whois lookup gives us the hosting provider. It may vary slightly depending on your source, but most tools will show the same ASN/organization.

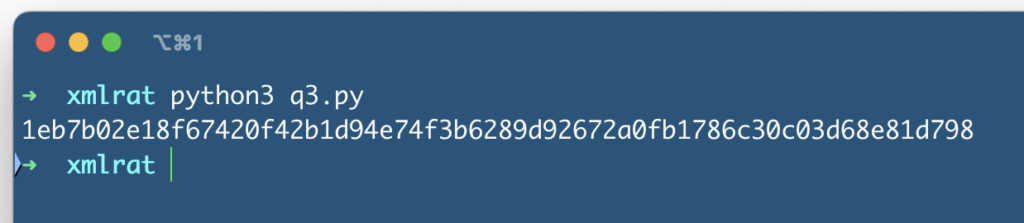

Q3: By analyzing the malicious scripts, two payloads were identified: a loader and a secondary executable. What is the SHA256 of the malware executable?

The malicious script contains a long hex blob stored in the $hexString_bbb variable which is the malware executable. Here’s how I approached it:

- Extract the value of the

$hexString_bbbvariable - Save it to a separate file (

mdm-payload.txtin my case) - Decode the hex string into binary

- Calculate a SHA-256 hash

- Hash it with Python

The script

import re

import hashlib

with open("mdm-payload.txt", "r", encoding="utf-8") as f:

text = f.read()

match = re.search(r'\$hexString_bbb\s*=\s*"([^"]+)"', text)

hex_string = match.group(1).replace('_', '')

binary_data = bytes.fromhex(hex_string)

# get the SHA256

sha256_hash = hashlib.sha256(binary_data).hexdigest()

print(sha256_hash)The script in action

If you want to reproduce my approach

Here’s what my mdm-payload.txt file starts with:

$hexString_bbb = "4D_5A_90_00_03_00_00_00_04_00_00_00_FF_FF_00_00_B8_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_40_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_...and here’s what it ends with:

...Sleep 5

[Byte[]] $NKbb = $hexString_bbb -split '_' | ForEach-Object { [byte]([convert]::ToInt32($_, 16)) }

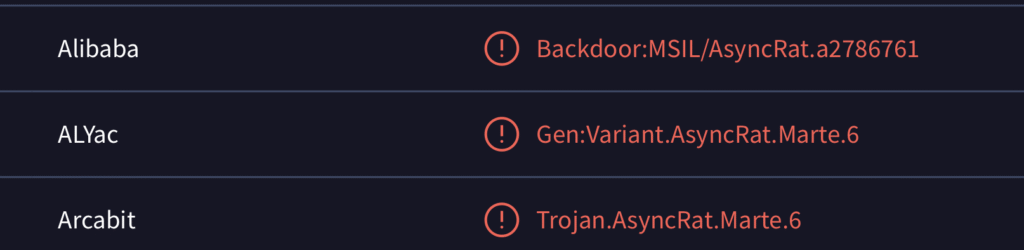

[Byte[]] $pe = $hexString_pe -split '_' | ForEach-Object { [byte]([convert]::ToInt32($_, 16)) }Q4: What is the malware family label based on Alibaba?

Let’s take the SHA256 hash from Q3, plug it into VirusTotal, and scroll to the “Security vendors’ analysis” section. Alibaba’s result usually shows within the first 12 or so entries.

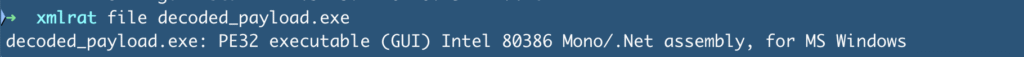

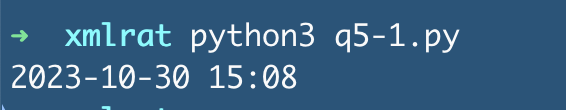

Q5: What is the timestamp of the malware’s creation?

This one was a bit more involved and required extracting the .exe payload to further analyze it.

Here’s the script I did it with:

import re

clean_hex_parts = []

with open("payload.txt", "r") as file:

for line in file:

parts = line.strip().split('_')

for part in parts:

part = part.strip().strip('"')

if re.fullmatch(r'[0-9A-Fa-f]{2}', part):

clean_hex_parts.append(part)

# convert to bytes

binary_data = bytes(int(b, 16) for b in clean_hex_parts)

# safe to FS

output_path = "decoded_payload.exe"

with open(output_path, "wb") as f:

f.write(binary_data)

Then, I checked how to look for timestamps using the PE header. With another bit of Python code:

from datetime import datetime

with open("decoded_payload.exe", "rb") as f:

data = f.read()

# PE header offset is typically found at 0x3C

pe_offset = int.from_bytes(data[0x3C:0x3C+4], byteorder='little')

# timestamp is 8 bytes after PE header start, so at offset pe_offset + 8

timestamp_raw = int.from_bytes(data[pe_offset + 8:pe_offset + 12], byteorder='little')

timestamp_human = datetime.utcfromtimestamp(timestamp_raw).strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M")

print(timestamp_human)It gives us the UTC creation date, or a rough estimate of when the executable was compiled.

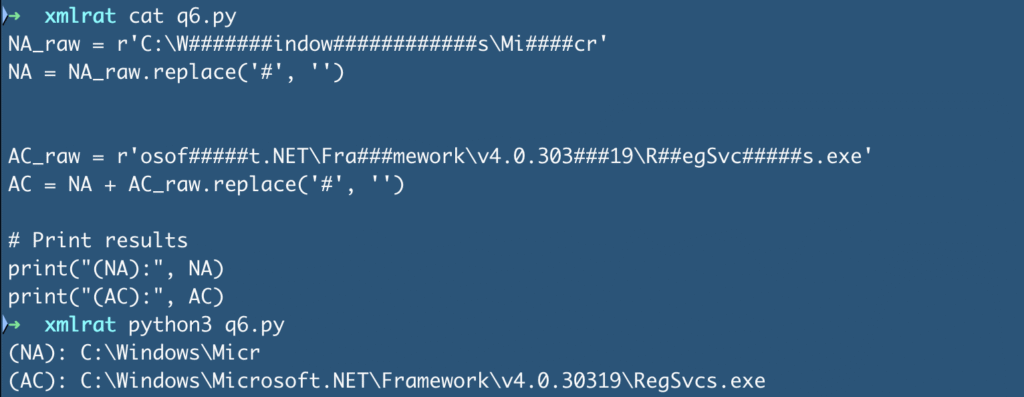

Q6: Which LOLBin is leveraged for stealthy process execution in this script? Provide the full path.

The script executes the malicious binary from memory without dropping it to disk, thereby helping the malware stay under the radar. The real stealth move is invoking a trusted LOLBin (Living-off-the-Land Binary) to “blend in”.

Let’s go Python again:

NA_raw = r'C:\W#######indow############s\Mi####cr'

NA = NA_raw.replace('#', '')

AC_raw = r'osof#####t.NET\Fra###mework\v4.0.303###19\R##egSvc#####s.exe'

AC = NA + AC_raw.replace('#', '')

print("(AC):", AC)

Q7: The script is designed to drop several files. List the names of the files dropped by the script.

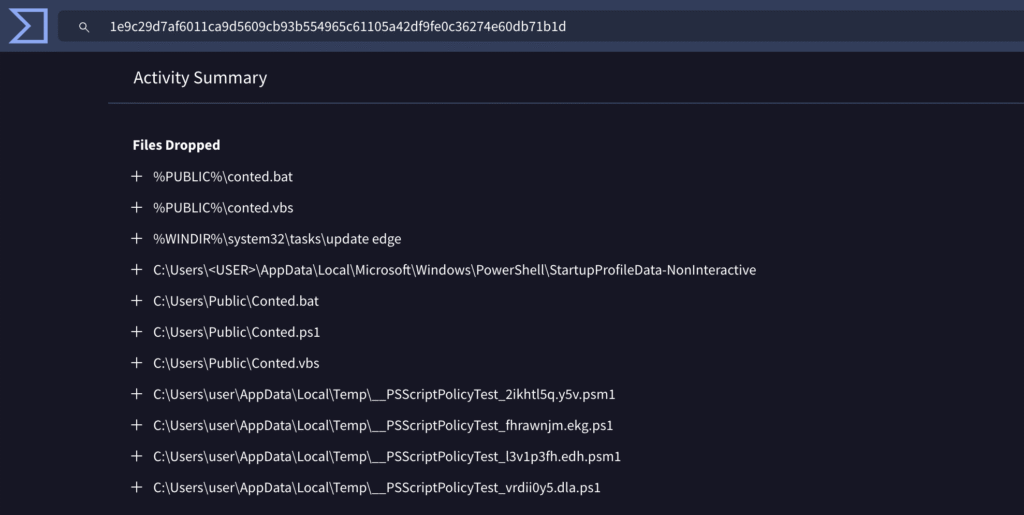

Back to VirusTotal. Let’s check under “Behavior” or “Relations” for dropped artifacts.

We see several files starting with Conted... – these are good candidates for the answer.

Phew!

This was a satisfying lab. The PCAP traffic gave us a thread to pull, but the real work came in decoding payloads and digging through obfuscated scripts. Less Wireshark than expected, more Python this time.

Big thanks to CyberDefenders and the authors of this challenge. You made reverse engineering fun again!

More about XLMRat

XLMRat is a modern Remote access trojan (RAT), named for its early use of Excel 4.0 macros (XLM) to infect systems. It’s often a variant of commodity RATs like AsyncRAT or Remcos, giving attackers full remote control over infected Windows machines.

Capabilities:

- Remote desktop, keystroke logging, file exfiltration

- Executes shell commands, injects into system processes

- Encrypted C2 (often via HTTPS), sometimes using Cloudflare tunnels

- Often acts as an initial access point for ransomware or full network compromise

Recent activity:

- Widely used in global phishing campaigns (2024–2025), often targeting orgs indiscriminately

- Shifted from macro-laden Excel files to HTML smuggling, malicious ISOs, OneNote notebooks, and scripts hidden in

.jpgor.txtfiles 👋 - Increasingly delivered in multi-stage dropper chains to evade detection

Evasion tactics:

- Heavy obfuscation (like the PowerShell hidden in image files)

- Uses LOLBins like

msiexec.exe,regsvr32.exe,rundll32.exe - Fileless execution, splits payload into chunks across files

- C2 often uses dynamic DNS, encrypted tunnels

What to do:

- Block dangerous file types in email (ISO, HTA, WSF, HTML)

- Disable all macros, including legacy XLM macros, in Office

- Enforce application whitelisting, block scripts from temp/download folders

- Use EDR that detects Office spawning PowerShell or script engines

- Patch systems quickly (especially Office and script engines)

- Train users to spot phishing and suspicious file types

- Isolate infected systems fast. RATs may precede full-scale attacks

A successful XLMRat infection can rapidly lead to data theft, credential compromise, and ransomware.